Europe’s last dictatorship may be heading towards a new direction, but towards which?

Last fall, I traveled from Warsaw to Brest and had to make a prolonged stop at the Polish-Belorussian border, where I was given an entry form in Cyrillic and forced to wait as my train wheels had to be changed to accommodate for the Soviet-era gauges still used in Belarus. As I waited, I looked from the entry form to the customs cost and it dawned on me how isolated Belarus remains nearly twenty years after its independence. The Belorussians preserve mementos of a bygone era on their trains as well as in every other aspect of their lives: it still celebrates the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, something even the Russians had forsaken. Soviet symbols were everywhere – some shockingly recent – and the state-run newspaper is still called Sovietskaya Belorussiya. In a country that vaunts the highest number of police per capita in Europe, the state intelligence bureau still chillingly retains its Communist moniker, the KGB.

On December 19th, the citizens of what has been dubbed ‘Europe’s last dictatorship’ will go to the polling booths and choose as their next president, Alexander Lukashenko or Alexander Lukashenko. With a comfortable economy and disorganized opposition, it is certain that Lukashenko will win his fourth term in office.

Lukashenko, a former military officer whose self-professed idol was Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Soviet secret police, first came to power in 1994 in the elections widely considered as free and fair. His law and order stance was widely popular in Belarus, then witnessing post-independent disenchantment and nostalgia for the certitudes of the former Soviet Union. In a run-off, Lukashenko won eighty percent of the vote – an overwhelming mandate that enabled him to slowly dismantle the democratic system that put him in power.

Once Lukashenko was in office, the brief economic reforms the Belarusians enjoyed in the early 90s were replaced by a Soviet-style planned economy. Although Lukashenko’s personality cult is almost negligible compared to those of other post-Soviet dictators (for instance in Central Asia), it is still lèse majesté to criticize Mr. Lukashenko in Belarus, and he won a referendum that would allow him – and only him – to run for unlimited number of presidential terms. In this half-Kafkaesque, half-Orwellian state, the Orthodox Church pledges allegiance to Lukashenko (as well as Moscow patriarchy) and Lukashenko appoints everyone from ministers to village store managers. Many opposition leaders and journalists died, ‘committed suicide’ under mysterious circumstances, or simply disappeared.

Mr. Lukashenko was a devoted Russophile; as a Belorussian apparatchik, he was the only deputy to vote against the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the Belorussian Soviet. Lukashenko entertained a vision for a pan-Slavonic state encompassing not only Belarus and Russia but extending from the Adriatic to the Bering Strait with himself as its president. During the Balkan wars in the late 90s, he suggested that Yugoslavia join the Union State, a loose confederation between Russia and Belarus.

Because of these credentials, Lukashenko enjoyed immense popularity in Russia in the 1990s. He unsuccessfully maneuvered for the top position at the Kremlin as the then-Russian President Boris Yeltsin floundered. Although far right elements in Russia perennially considered Lukashenko as a potential presidential candidate, Lukashenko seems an anachronistic caricature in Putin’s Russia. With his ambition hampered, Lukashenko viewed the subsequent occupants of the Kremlin as adversaries, although Belarus increasingly depended on Russia for much of its trade.

Putin might be the reason Mr. Lukashenko seems to be slowly turning against Moscow. In 2009, he ignored a Russian gas price increase and underpaid; when the Russians cut gas supplies to Belarus, Lukashenko countered by a cut of his own: stopping transit shipments of Russian gas to the EU. In other arenas too, there are increasing signs that Moscow is slowly losing control of its protégée: Lukashenko refused to recognize the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and also decided to shelter Kurmanbek Bakiyev, the deposed leader of Kyrgyzstan loathed by Moscow. Lukashenko delayed a customs union among Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus much wanted by Russia, and threatened to deny Russia a lucrative contract to build the first nuclear power plant in Belarus.

Last week, in his video blog, President Dmitri Medvedev spoke out: “The Belarusian leadership has always been characterized by a desire to create an external enemy image in the public consciousness. The United States, Europe, and the Western countries acted as such ‘enemies’ earlier. Now Russia is declared the enemy.” Moscow also fought back by banning Belarusian exports, and then by hypocritically denouncing the lack of media-freedom and democracy in Belarus. The upcoming presidential elections may yet be Russia’s biggest weapon: its state-controlled media has been airing documentaries critical of Alexander Lukashenko, and it has been speculated that Moscow might fund Andrei Sannikov, the opposition leader who is not too close to the West.

The elections also come at a crucial time for the international community, which recently abandoned its isolation of Belarus. When Russia cancelled its $500 million aid to Belarus, the IMF stepped in with an additional $1 billion loan. In 2009, Belarus was included in the EU’s Eastern Partnership Initiative, which serves to strengthen economic and political ties between Europe and six former Soviet states. Lukashenko’s travel ban to Europe was also lifted. In return, Lukashenko released a large group of political prisoners.

For the last fifteen years, Belarus served as Russia’s buffer state; Russia maintains electronic warning stations and radars in Belarus, as well as an important nuclear submarine control center in Vileyka. Overall, Russia would benefit from a friendly leader in Belarus and that was the reason Russia supported Lukashenko despite allegations of vote rigging by the West in the last presidential elections in 2006.

In this election, however, Russia may be forced to make the unpalatable political choice between Lukashenko and any of his less mercurial but also less-Russophilic opponents. It is likely that Russia may merely threaten Mr. Lukashenko rather than actually transfer their support elsewhere. Although it is unlikely, it would also be a bold personal move for Mr. Medvedev if he refused to recognize the election results. But, the Russian leadership has always considered Belarus to be in Russia’s backyard, and it will do everything to prevent any unfavorable outcomes there, even if it means creating yet another volatile political situation in the region.

— The Archer

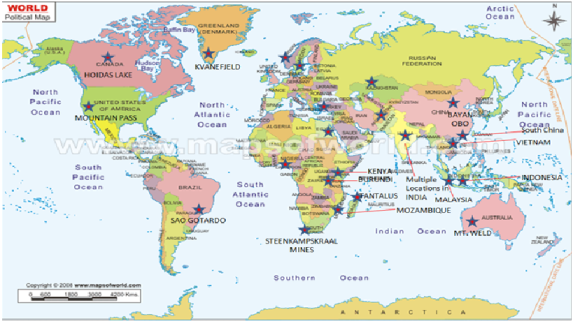

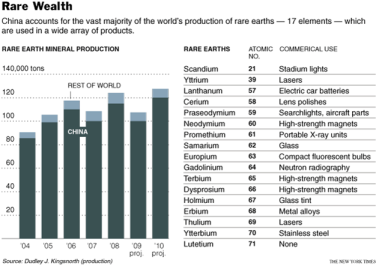

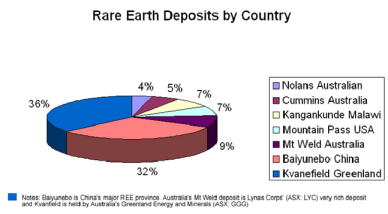

Deposits outside of China, however, are rarely worked. As the 2010 U.S. Geological Survey of Mineral Commodity Summaries indicates, while 120,000 tons of rare earth production came from China, only 2,700 tons came from India, and only 650 tons from Brazil. No production was recorded from the United States or Australia in 2009. Surprisingly, Greenland with its Kvanefjeld Mines was absent from the list as well. The government of Denmark, which controlled all oil, gas and mineral resources in Greenland until early 2010, has opposed all resource extraction that involves radioactive materials which are usually found in association with rare earth minerals

Deposits outside of China, however, are rarely worked. As the 2010 U.S. Geological Survey of Mineral Commodity Summaries indicates, while 120,000 tons of rare earth production came from China, only 2,700 tons came from India, and only 650 tons from Brazil. No production was recorded from the United States or Australia in 2009. Surprisingly, Greenland with its Kvanefjeld Mines was absent from the list as well. The government of Denmark, which controlled all oil, gas and mineral resources in Greenland until early 2010, has opposed all resource extraction that involves radioactive materials which are usually found in association with rare earth minerals

The New York Times

The New York Times

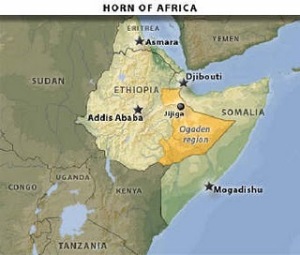

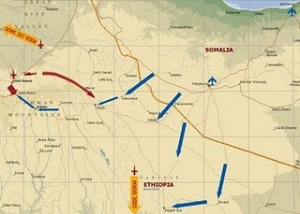

The attack killed 65 Ethiopians and nine Chinese workers. In response, the Ethiopian government imposed a blockade to prevent supplies from reaching the rebels across the porous Ethiopia-Somalia border region. In addition, the government initiated a major counter-insurgency operation, calling on local leaders to mobilize their clans to form militias and

The attack killed 65 Ethiopians and nine Chinese workers. In response, the Ethiopian government imposed a blockade to prevent supplies from reaching the rebels across the porous Ethiopia-Somalia border region. In addition, the government initiated a major counter-insurgency operation, calling on local leaders to mobilize their clans to form militias and